“Knowing just burdens my heart,” said my longtime friend, an elementary school teacher in eastern Oregon. “I have 26 other babies to take care of!”

Over the years, I’ve heard many other teachers express the same sense of overwhelm. With all the demands placed on them today, they’re often simultaneously expected to adequately support students with severe trauma.

Yet there my friend was dealing with a boy in need who was acting out in ways that would derail her whole classroom – in a financially strapped district with little support to offer.

Teachers can’t be expected to be counselors or social workers, too. But with increasing societal stress and rising numbers of kids with mental health issues, new classroom management strategies and tools are needed.

Trauma-Informed Classrooms or Trauma-Resilient?

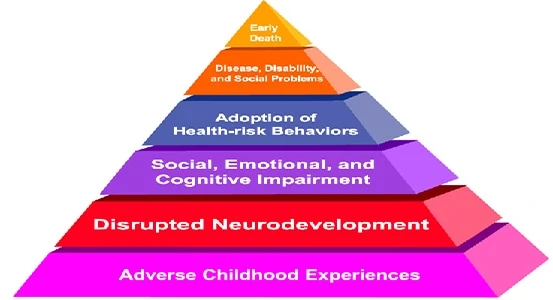

While the growing awareness of trauma and its effects has been a welcome change in education, there is often too much focus on risk and not enough on resilience. We hear about all the terrible things that can happen, such as a greater propensity toward self-destructive behavior and chronic illness.

We hear far less about how to specifically build resilience.

Let’s face it: All of us, throughout our lives, will encounter traumatic experiences, directly or vicariously. And given the ACE research, we can also safely assume that a significant number of our students (from any income bracket) will have directly experienced trauma.

So what can we do to help kids in need, in the context of today’s classroom environment?

Start with Ourselves

Understanding what happens to our brains and bodies in the continuum from stress to trauma is an important first step – and something we explore in-depth in my Transforming Childhood Trauma online course, but one that’s often overlooked is teacher self-care.

Since children reflect the nervous systems of adults around them, teacher self-care provides the foundation for the teacher-student relationship and ultimately supports all student behavior and learning. Modeling what we teach, we include components of self care in all our trainings, but our new Back in Balance: Self Care for Body, Mind & Heart workshop is designed to address it directly. Designed with teachers in mind, this workshop will help you explore practical ways to honor and care for yourself while you attune to the needs of your students.

When we practice self-care we are then more likely to communicate safety to those around us with calm and regulated vocalization, visual contact, and facial expressions. As Dr. Steven Porges has shown through his work on the “social nervous system,” these responses support nervous system regulation in others and can mitigate children’s more extreme Fight/Flight/Freeze responses.

Mindful Movement Releases the Effects of Stress & Trauma

A more effective approach, as we’ve noted before, involves the whole body.

Simple, slow, repetitive, rhythmic movement in a safe environment – such as in the practice of yoga – has been found by trauma recovery experts such as Drs. Bruce Perry and Bessel van der Kolk to help calm the brainstem and amygdala, and help us regulate. Why? Such movement

- Honors they body’s need to move or change the situation.

- Unwinds the “flexor response” or natural urge to pull towards a fetal position with stress.

- Provides deep proprioceptive and vestibular nervous system input that calms the amygdala and helps turn on the prefrontal cortex (“upstairs brain”).

- Burns off the stress hormone cortisol.

- Provides a sense of control and self-efficacy.

- Sensate awareness also helps to bring us into the present moment and helps “unfreeze” those who dissociate in response to stress.

Combine this with students choosing and leading the movement flows, in an emotionally-supportive environment, and you meet stress researcher Dr. Robert Sapolsky four keys to stress managment:

- Develop social affiliation and support

- Create a sense of control (or perceived sense of control)

- Find regular outlets for frustration

- Develop a positive outlook and emotional skills

Prevention, Not Just Intervention

Earlier this month, the CDC released a new report on how preventive strategies might improve public health with respect to trauma. Among their recommendations?

Enhancing skills to help parents and youths handle stress, manage emotions, and tackle everyday challenges.

Providing daily playful experiences that include movement and social support in a safe context with a regulated parent, caregiver or teacher accomplishes just that. And for the classroom, not only does it reduce stress and address trauma; it’s good for learning in general.

Mindful movement processes can also set the stage for more cognitive, seated mindfulness practices and SEL lessons that encourage greater personal reflection and social awareness.

So, why wait? These practices are easy to implement, cost little, and are well received by students. They make you and them feel better, too, helping with classroom management and reducing the need for extreme interventions.

And they help all students in your class, but particularly those who really need it the most.

Bottom two photos courtesy of 1000 Petals