Recently, Lynea and I were asked to speak at a conference about technology’s impact on education. Immediately, my thoughts turned to what we feel is one of the greatest challenges facing us as educators and parents: the addictive nature of electronic media and its associated health and social effects.

For what we’ve found is that – for youth and adults alike – increased screen time comes at the expense of sleep, which contributes to behavior issues, obesity and learning difficulties. At the same time, electronic media are changing the very structure and function of our brains. The constant stimulation and distraction encourages multitasking, fueling a continuous stress response. More, all this screen time comes at the expense of the face-to-face social interactions through which we develop important social and emotional skills, learn compassion and how to work together…

Then it hit me: The symposium series wasn’t about this “dark side” of technology but how to get kids to use even more of it in the classroom.

Now, I’m no Luddite. In fact, one third of my working life was in the telecom industry, developing technological solutions to problems. Yet what I’ve learned over the years is that technology is neither inherently good or bad, but neutral. Its promise – and its danger – is that it amplifies human intent.

Recent reports about the efficacy of educational technology lend weight to this. What are we getting from the billions of dollars we spend on classroom tech? Do we see a boost in academic achievement? The results are mixed, some say disappointing:

“The data is pretty weak. It’s very difficult when we’re pressed to come up with convincing data,” said Tom Vander Ark, the former executive director for education at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and an investor in educational technology companies.

Critics counter that, absent clear proof, schools are being motivated by a blind faith in technology and an overemphasis on digital skills — like using PowerPoint and multimedia tools — at the expense of math, reading and writing fundamentals. They say the technology advocates have it backward when they press to upgrade first and ask questions later.

The problems today require a different mind

than the one that got us here in the first place…. – Einstein

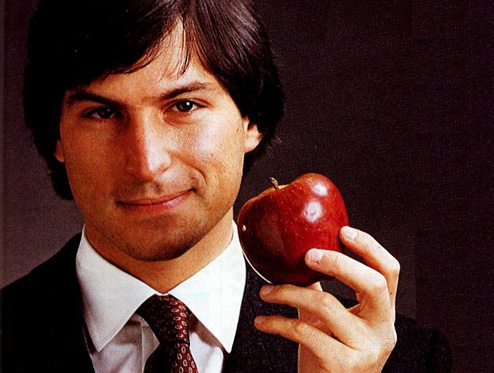

Enter our modern day Einstein, Steve Jobs.

Even months since his passing, people continue to reflect on Jobs’s accomplishments and legacy. What was it about him that led to revolutions in computing and technology design, dramatically altering the way we work, play, connect and live?

Walter Isaacson’s remembrance speaks volumes:

Was Mr. Jobs smart? Not conventionally. Instead, he was a genius. That may seem like a silly word game, but in fact his success dramatizes an interesting distinction between intelligence and genius. His imaginative leaps were instinctive, unexpected, and at times magical. They were sparked by intuition, not analytic rigor. Trained in Zen Buddhism, Mr. Jobs came to value experiential wisdom over empirical analysis. He didn’t study data or crunch numbers but like a pathfinder, he could sniff the winds and sense what lay ahead.

He told me he began to appreciate the power of intuition, in contrast to what he called “Western rational thought,” when he wandered around India after dropping out of college. “The people in the Indian countryside don’t use their intellect like we do,” he said. “They use their intuition instead … Intuition is a very powerful thing, more powerful than intellect, in my opinion. That’s had a big impact on my work.”

Mr. Jobs’s intuition was based not on conventional learning but on experiential wisdom. He also had a lot of imagination and knew how to apply it. As Einstein said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge.”

This connection between imagination – intuitive, creative vision – and accomplishment is both surprising and not. If we think of imagination as separate from “smarts,” then yes, it’s surprising. But they are, in fact, intricately unified. It’s why we stress the integration of physical, cognitive and emotional learning. Why we need to look beyond just cognitive learning to create tools that address the needs of the whole child in a holistic way. And the results speak for themselves: higher test scores, fewer behavior referrals, stronger learning communities, happier children and teachers.

Interestingly, the stuff of Jobs’s world – technology – consistently fails to generate the academic improvement we’re all longing to see.

Even Mr. Jobs, Apple’s co-founder, turned skeptical about technology’s ability to improve education. In a new biography of Mr. Jobs, the book’s author, Walter Isaacson, describes a conversation earlier this year between the ailing Mr. Jobs and Bill Gates, the Microsoft co-founder, in which the two men “agreed that computers had, so far, made surprisingly little impact on schools — far less than on other realms of society such as media and medicine and law.”

The comments echo similar ones Mr. Jobs made in 1996, between his two stints at Apple. In an interview with Wired magazine, Mr. Jobs said that “what’s wrong with education cannot be fixed with technology,” even though he had himself “spearheaded giving away more computer equipment to schools than anybody else on the planet.”

So perhaps it’s another non-surprise that plenty of techies take a decidedly low-tech approach to their own children’s education. At the Waldorf school in Los Altos, California, for instance, 3/4 of the students have parents with strong industry ties. As one of those parents – a Google executive– told the New York Times, “The idea that an app on an iPad can better teach my kids to read or do arithmetic, that’s ridiculous.”

Furman University education professor Paul Thomas would agree, noting in the same article that “a spare approach to technology in the classroom will always benefit learning. [For] teaching is a human experience. Technology is a distraction when we need literacy, numeracy and critical thinking.”

Thus, the need for a humanistic approach in the classroom – to cultivate conscience and character while instilling knowledge and teaching skills. Then, when we do incorporate technology, students may be more apt to use it well.

This, I think, is the real message of Steve Jobs: We don’t necessarily need more technology; we need more creativity and vision.

Dominic Randolph is one educator putting those to work, complementing academic rigor with social-emotional learning (SEL). As headmaster of New York’s prestigious Riverdale School, Randolph

did away with Advanced Placement classes in the high school soon after he arrived at Riverdale; he encourages his teachers to limit the homework they assign; and he says that the standardized tests that Riverdale and other private schools require for admission to kindergarten and to middle school are “a patently unfair system” because they evaluate students almost entirely by I.Q. “This push on tests,” he told me, “is missing out on some serious parts of what it means to be a successful human.”

The most critical missing piece, Randolph explained as we sat in his office last fall, is character…

He’s since implemented a complementary curriculum focused on nurturing strengths identified by Martin Seligman and others that have been deemed necessary for resiliency, happiness and success. It’s the focus of a long New York Times Magazine article that’s definitely worth your time, detailing the program and reactions to this new emphasis on SEL’s role in education. (You can read the whole thing here.)

Results at Riverside, as in Yoga Calm classrooms around the world, just underscore the point that such programs are a better investment than computers and software. They’re less expensive; don’t break down, don’t get infected or act buggy; don’t require lots of expensive peripherals to use. And instead of focusing on just one area of improvement, programs like Yoga Calm support improvement across the board, for you’re educating the whole child.

Perhaps dedication – or rededication – to this concept is the best and most selfless resolution any of us can make for the incipient New Year.

Image Credits

boy at screen by Paul Mayne, via Flickr

young Steve Jobs, via epicaGear

character sign, via educationkorner.com