It’s easy to think that if something works for us, it will work for anyone. How could the action that brought us peace, say, or joy not bring that same good feeling to everyone who tries it?

We come to each moment from our own history, our own tastes, our own habits, our own way of understanding the world. While there is so much that we share, so much that connects us with each other, there’s no one-size-fits-all way of pursuing anything.

Take mindfulness.

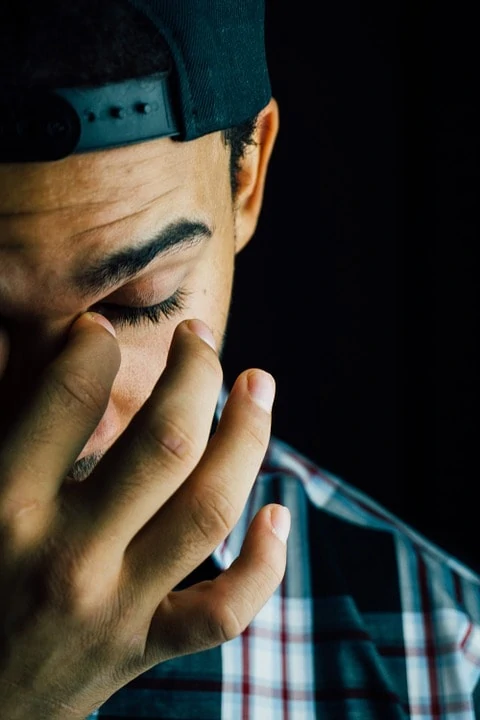

While we all know the image of a person sitting, eyes closed, breathing with a deep calm, that meditative state is just one way of practice. And it can be difficult for someone with a history of trauma, when we focus on the sensations of the body.

For those who have experienced trauma, the practice of mindfulness can become physically intolerable. The physical sensations experienced as the mind turns to focus on itself are overwhelming; to a point where intense agitation and physical pain or illness occur. For others with PTSD, the experience of physical discomfort has meant that they have learnt to dissociate themselves from feeling anything at all. The benefits of mindfulness then become inaccessible.

When Mindfulness Can Become Triggering

When we introduce mindfulness to the classroom, it’s important to remember that roughly half of all students have experienced at least one adverse childhood event. A good number may be experiencing one right now – from parents separating to homelessness, substance abuse in the family to sexual abuse.

Where trauma is in play, such “bad behavior” may be better understood as a trigger or coping mechanism, however ineffective or even destructive it may seem. It’s a way to protect oneself when feeling threatened – even by something as seemingly benign as closing one’s eyes.

Trauma-Informed Mindfulness

It’s interesting to note that in the yoga tradition, meditation practices weren’t the first skills to be taught. Instead, they often followed training in social mores, physical movement, and breathing practices. I think there is wisdom to that, especially when it comes to teaching mindfulness for trauma recovery.

Secondly, trauma is held in the body, and that needs to be addressed early on. The world’s foremost trauma researchers, including Bessel van der Kolk, PhD, and Dr. Bruce Perry, recommend yoga and other “bottom-up” (sensory motor/brainstem-based) approaches as beginning treatment for traumatized children.

The physical discharge of tension and calming of the amygdala turns on the “thinking brain” (prefrontal cortex), which is not only key for trauma survivors but useful for all students to help them regulate their nervous systems, build resilience, and inoculate them from the effects of stress.

Body-based practices also help trauma survivors to explore present-oriented experience in the context of playful sensory motor experiences – further developing arousal regulation skills and their “Window of Tolerance” (Siegel, 1999). And these activities are just as beneficial for the adults that teach them to help keep us regulated, too!

Thirdly, combining physical movement with supportive cognitive themes like our Yoga Calm Strength principle, as well as student leadership and choice, can help kids develop a sense of control and efficacy – another key aspect of trauma recovery.

The routine of all these activities provides a reliability they need, as well. Often, trauma survivors are coming from environments where chaos was or is the norm, where stability may be fleeting. Yoga Calm becomes something they learn they can rely on; their teacher and classmates, as well.

Over time, they may find it easier to close their eyes during a Mindful Moment or guided relaxation. Or they may choose to keep their eyes open. There are, as we’ve noted, many ways of mindfulness.

Click here for General Guidelines & Tools for Working with Trauma from our online course Transforming Childhood Trauma.

Community building image by US Army