By Lynea Gillen

“We know you’ve had challenges,” I told them. “And we know that you’re very strong because of them. We’d like to hear about your strength. Tell us your stories.”

And as they did, the atmosphere in that room shifted. The young men transformed from victims into young warriors.

By the end of the class, we knew them as musicians and poets and writers. We knew how they felt connected to often villainized animals – cougars and foxes and wolves. We knew of their journeys and the strength and bravery it took to travel them.

Helping them see their experiences as heroic changed the stories they told about themselves and their trauma, encouraging their healing. The key? Focus on strength.

Trauma Changes the Developing Brain

“You see deficits in your ability to regulate emotions in adaptive ways as a result of stress,” said Dr. Cara Wellman, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at Indiana University.

Dendrites, which look like microscopic fingers, stretch off each brain cell to catch information. Wellman’s studies in mice show that chronic stress causes these fingers to shrink, changing the way the brain works. She found deficiencies in the pre-frontal cortex – the part of the brain needed to solve problems, which is crucial to learning.”

Other researchers link chronic stress to a host of cognitive effects, including trouble with attention, concentration, memory and creativity.

Recognizing this, more schools have shifted to a “trauma-informed” approach, focusing less on “bad” behavior, more on the issues that drive the behavior. In fact, there is

a national trend, driven by a massive, landmark public-health study called Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs, which showed that trauma, even among the study’s relatively middle-class participants, is far more common than previously believed.

The study found that almost two-thirds of adults experienced at least one traumatic event during childhood, through exposure to violence or personal abuse and neglect, findings since replicated by a number of other large studies.

Educators’ shift in attitude toward traumatized students has been hastened by parallel research showing that repeated or prolonged trauma can actually change a child’s brain. Neuroscientists have found that those altered brains — adapted for survival in the worst conditions — may cause traumatized children to react differently, struggling to connect with peers and adults and wrestling with basic language development and learning.

In other words, unaddressed trauma is an educational problem. Students consumed by sadness or anger are often unable to focus on learning.

Thus, the solution: Address the trauma.

A Strength-Based Approach to Trauma

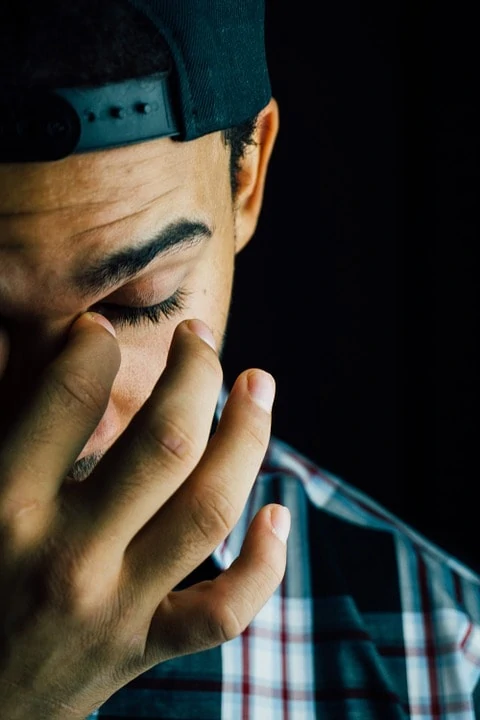

Trauma is marked by a lack of safety and stability. Violence, abuse, poverty, homelessness, and other such destabilizing crises are, in fact, a kind of theft – a theft of security. Left in its place are challenging emotions such as fear, anger, and anxiety.

But intervention also means addressing the core components of complex trauma intervention identified by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. These include restoring a sense of safety, enhancing self-regulation, and developing ability to direct one’s attention.

Since stress and trauma reside in, and manifest through, the body’s physiology, learning to notice, tolerate, and manage somatic experience can substantially promote emotion regulation. Yoga, mindfulness and TRE® (Trauma Releasing Exercise) practices do just that – practices we teach in courses like our Transforming Childhood Trauma course.

Importantly, the skills children learn when we help them from a strength-based approach are skills that can serve far beyond the immediate task of healing from their own trauma.

Strength Pays It Forward

While school social worker Mary T. Schmitz was completing her Yoga Calm certification, a tragedy hit her town and school. A mother drowned her two children and committed suicide. The children were students at Mary T.’s school. The mother had been a volunteer there. In fact, she had been there just a week before the killing.

Mary T. was part of the crisis response team called upon to support the second grade classroom in which one of murdered children had been a study. One of the tools she brought was Yoga Calm.

A schoolwide memory event was discussed, but some felt that it would be “too much” for the younger kids to handle. Mary T. suggested having the second graders she had worked with teach what they had learned to the others in their grade. Staff were included, as well, especially the resistant ones. This beautiful moment of peers helping peers ultimately led to a district-wide buy-in of Yoga Calm and mindfulness training. Mary T. now trains others as her school’s Mindfulness Education Specialist. Even the principal is now certified in Yoga Calm! (Hear what students, parents, and others have to say about the implementation.)

But that’s not all of the story.

A few years later, the best friend and classmate of one of the murdered children was set to go to Girl Scout Camp. Her mom was a little apprehensive about it, concerned about her daughter’s possible anxiety. But while she went and was fine, many of the other girls were experiencing a lot of anxiety and homesickness.

The girl stepped up and volunteered to teach what she knew – the Yoga Calm she had learned back in second grade. When her mom later asked her about it, she said, “I just taught them what Mary T. taught us – how to go into Mountain.”

Join us in Portland, OR, April 29-30, 2017 for Transforming Childhood Trauma: Healing Heart, Mind & Body. CEUs, clock hours and graduate college credit are available. Full course description and registration info here.