The other day, we noticed that our “Focusing Fun” segment from the Flying Eagle DVD – a demonstration of a simple game to practice focus – has now been seen by almost a million people. One million!

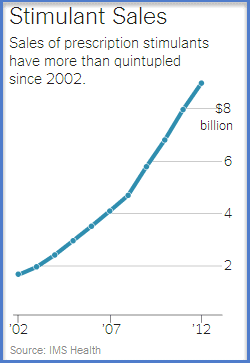

Clearly, folks are looking for help with addressing ADHD symptoms beyond medication. A simple Google search brings up pages and pages of tips sheets and strategy guides. Just one of our posts on nurturing focus and self-control in kids diagnosed with ADHD has been viewed by roughly 20,000 people.

You also see parents, teachers, therapists, and others share what has worked for them, such as in this compendium from Edutopia. But while the tools suggested in articles such as this – everything from squeeze balls to standing desks to yoga balls and beyond – can be helpful for challenging energy in non-distracting ways, reliance on them can overlook a critical fact: What is needed is movement – not just for “ADHD kids” but all kids.

Canaries in the Coal Mine of Our Sedentary Culture

Just this past week, we learned of a new study on screen time and ADHD symptoms. Over two years, researchers tracked ADHD symptoms and digital media habits of more than 2500 Los Angeles high school students. At the start of the study, none had symptoms of ADHD. By the end of it?

Teens who reported frequent use of a wide variety of digital media platforms at the start of the study, however, were about 10% more likely to develop ADHD symptoms within the next 2 years, researchers reported July 17 in JAMA.

While the study doesn’t show cause and effect, when you consider how mobile devices especially can be sources of interruption and distraction, and how quickly most media jumps from one view to another (about every 2 seconds for the typical TV show or film), it’s easy to see how how a person may become conditioned to be more easily distracted.

Already, there’s a tendency toward fidgetiness when kids are told to sit still and pay attention. But as we’ve discussed before, this may not always be ADHD but simply the wisdom of the body making itself heard. Kids in a classroom eventually start to fidget because they need to move.

Brain and body work together, and a growing body of research continues to demonstrate that physical activity supports cognitive health. For optimum learning, movement is required.

The Need for More Breaks

Through recent years, we’ve heard a lot about the amazing school system in Finland, a model of successful education. There are plenty of differences between their system and ours, but one of the most notable is that the students get breaks much more frequently. For every 45 minutes of instruction, they get a 15 minute break.

In his book Teach Like Finland, American educator Timothy Walker describes how he initially resisted the frequent breaks after he began teaching in that nation – to disastrous results. But, he writes,

Once I incorporated these short recesses into our timetable, I no longer saw feet-dragging, zombie-like kids in my classroom. Throughout the school year, my Finnish students would, without fail, enter the classroom with a bounce in their steps after a fifteen-minute break. And most important, they were more focused during lessons.

A good body of research bears this out. Among that which Walker cites is the work of educational psychology professor Anthony Pellegrini.

Not satisfied with anecdotal evidence alone, Pellegrini and his colleagues ran a series of experiments at a U.S. public elementary school to explore the relationship between recess timing and attentiveness in the classroom. In every one of the experiments, students were more attentive after a break than before a break. They also found that the children were less focused when the timing of the break was delayed—or in other words, when the lesson dragged on (Pellegrini, 2005). [emphasis added]

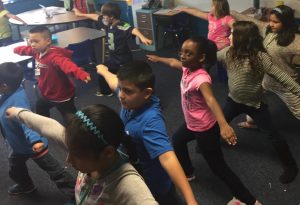

Importantly, the breaks don’t need to be full school, outdoor recess as we usually think about it. It’s the breaks themselves that matter, giving the brain a chance to refresh itself and giving kids opportunities to move. Adding short yoga flows between class segments, for instance, could do wonders.

Movement & Learning

Yoga was associated with modest improvements on an objective measure of attention (KiTAP) and selective improvements on parent ratings.

The results also showed that “school yoga worked better when practised in the classroom” rather than other locations.

Another recent study, this out of Tulane, confirmed what other research has shown about the impact of school-based yoga:

it reduces student stress and that joins other research reporting it has benefits ranging from improved performance in class and on tests, and more helps students have more control over problems with attention, inappropriate behavior and conflict. By practicing it with the class or on their own teachers would de-stress too, experts say.

So why not add movement breaks for ALL kids in your class in the coming school year? Not only may it help (and normalize) the “ADHD kids;” it can benefit all the children – and yourself, too.

Texting image by D. Sinclair Terrasidius, via Flickr

Good info and timely.